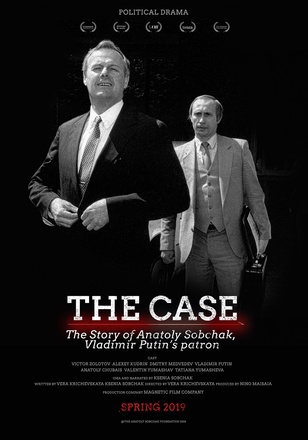

2019 | Documentary | 105 min. | Russia

The story of Anatoly Sobchak, Vladimir Putin’s patron. The central figure of The Case is Anatoly Sobchak. He was a democrat of the first wave in Gorbachev era and the first mayor of St.-Petersburg who ironically brought Vladimir Putin into power. Ksenia Sobchak, a daughter of Anatoly Sobchak, is a protagonist. In the beginning of the documentary, Ksenia describes the film as an attempt to reconstruct the events of the last 10 years of her father’s life when she was just a kid. Ksenia tries to answer the questions why pro-democracy activist Sobchak brought Vladimir Putin, a KGB officer, into power and why Boris Yeltsin chose Putin as his successor. We uncover the events of the power succession, untold special agent Putin's operation and Sobchak’s pivotal role in it and the effect of the criminal case against him. The reconstruction helps to figure out how and why Vladimir Putin got into the Kremlin. Ksenia lacks her own memories and understanding of many events. She rebuilds her father’s story step by step. This story evolves not only into the history of the country and early years of democracy in Russia, but also into a thriller with special operations, arrests and dismissals. For the first time ever, we investigate why democracy supporters split shortly before the presidential elections in 1996. It was their split that made security forces representatives’ coming into power possible later in 2000. Ksenia finally has got the access to the criminal case file against her father. The well-known and respectful lawyers who have reviewed it conclude that he was completely innocent. As Anatoly Sobchak’s career declines, the film depicts a vivid picture of how the security establishment, army generals and KGB chiefs, conspired against him. We see how, step by step, they regained the ground they lost under Gorbachev. When Sobchak was forced to emigrate, this was a big victory for the security establishment. At the same time, the Film describes the experience that Vladimir Putin got from his work with Sobchak. He could see where press freedom, free elections and real election debate lead. He realized that those in the inner circle could become traitors. The political experience of Sobchak’s fall seems to have been one of the main lessons learned by Vladimir Putin, the lesson of what NOT to do. It is an experience of failure. The speakers in the film include Russian top politicians and security officials, such as Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Medvedev and Victor Zolotov, the current Director of the National Guard of Russia (Rosgvardiya), who was Anatoly Sobchak and Ksenia Sobchak’s bodyguard for many years. This is his first interview. Other speakers include members of Sobchak’s team in Saint-Petersburg and President Yeltsin’s inner circle - two Heads of his administration and chief of President Yeltsin Security service.

Directors Statement

For years, I’ve been asking myself the same question that many of my friends and, generally, people who share similar views: how could this all happen to Russia? How is it possible that 25 years after winning fundamental civil freedoms, we left them and ended up in isolation, branded as the world’s bully? How did it all happen? In 1989, the year that velvet revolutions swept across Eastern Europe and the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, I started out as a reporter in St. Petersburg – back then, still Leningrad – at a new local independent newspaper. That year, Anatoly Sobchak became a star – and not just in our city but throughout the Soviet Union. He was the most unconventional among Soviet politicians. His very appearance, you might say, promoted western values and civil freedoms. In 1991, we all – my friends, colleagues and myself – followed him, unarmed, determined to stop tanks from entering St. Petersburg. And it was this man, the legend and the symbol of the early 1990s, the nemesis of bureaucrats and security officials, who brought Vladimir Putin into the world of politics. Together with Ksenia Sobchak, we set out to figure out this historical paradox, which resulted essentially in the same person staying president practically for five terms. Over the last 19 years, after Putin, Sobchak’s former aide, became acting prime minister, he was asked on numerous occasions what he was doing in St. Petersburg on November 6, 1997. Every time, Vladimir Putin would give a clear answer, and it is even recorded in his official biography: “It was a national holiday, and I went to St. Petersburg to visit my family.” In the fall of 2017, when we were making a documentary about Sobchak, Vladimir Putin told us – for the first time ever – what was really going on that day, November 6, 1997. What happened on that day, essentially, decided Putin’s future and brought him to the Kremlin in 2000. The incident, which we describe in our film in detail, identifies the triangle – Yeltsin-Sobchak-Putin, which in a paradoxical way defines the plot of the film. It also explains why Boris Yeltsin and his entourage, who held rather liberal views, picked Vladimir Putin, Sobchak’s aide, as the next leader. This transition of power in Russia has never been explained in such detail and yet so simply. After watching our film, many people in Russia said as they were leaving the movie theater that all the pieces of the puzzle had finally fallen into place. As Anatoly Sobchak’s career declines, the film depicts a vivid picture of how the security establishment, army generals and KGB chiefs, conspired against him. We see how, step by step, they regained the ground they lost under Gorbachev. When Sobchak was forced to emigrate, this was a big victory for the security establishment. Our film is about historical experience – the experience we should gain as viewers, voters and citizens. And, more importantly, it is about the experience that Vladimir Putin got from his mentor, Anatoly Sobchak. There is a character in our film who says, “If he [Putin] took the same way as Sobchak, he would end up like Sobchak. But he is in the Kremlin.” We recorded over 30 multi-hour interviews with the key participants in the events described in the film. Each of these people can be described as a first-hand source. In these interviews, we did our best to establish all the facts. We understood that each person has own version of the events, and each one sees the story differently. We only used the reports, which could be corroborated by at least two more sources. Apart from top-level government officials, we interviewed Russia’s two top security guards – the chiefs of Boris Yeltsin’s and Vladimir Putin’s security services. The former sought to influence the decision-making process in Russia in the 1990s, while the latter is top security official in Russia today, and this was his first interview ever. President Yeltsin’s chiefs of staff, his daughter Tatyana and Boris Nemtsov, a deputy prime minister in the 1990s who was shot dead three years ago right next to the Kremlin – all these people tell their stories in the film next to the new elite of the Putin era. And this creates yet another paradox: for example, in 1997, Boris Nemtsov was one of the few people who tried to help Sobchak and was acting on Vladimir Putin’s side. We spent 18 months reviewing footage of St. Petersburg from the 1990s. In the course of this work we were contacted by people who found boxes with Betacam tapes labeled “Sobchak” somewhere in their attic. The boxes happened to contain an invaluable archive, which we returned to the owners and used in the film. We went over dozens of VHS tapes from the Sobchak family archive and found unique footage of St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and his aide Vladimir Putin spending their summer holidays in Finland together. Those videos have never been shown before. It is this archive footage that added depth to the two main characters. To me, this film is a trip down memory lane, a chance to return to the 1990s, the times of freedom I was part of. It is also a historical lesson we are yet to learn. Vera Krichevskaya, Director and co-writer of The Case (Delo Sobchaka)

Director: Vera Krichevskaya

Producers: Nino Maisaia and Dmitriy Grishin

Сast: Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Medvedev, Victor Zolotov, Alexander Korzhakov, Tatiana Yumasheva, Sati Spivakova, Alexey Kudrin, Anatoly Chubais, Valentin Yumashev and Sergey Filatov

Studio: Magnetic