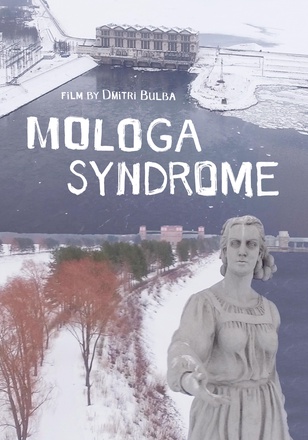

2017 | Documentary | 45 min. | Russia

Some of the last surviving natives of the flooded city of Mologa live in Rybinsk. And they have things to remember: the dekulakization of their families, the repression of their parents, eviction and war. In a strange way, their recollections overlap with contemporary holidays commemorating Victory Day and the day of remembrance for the lost city, creating a sensation of an entirely different past.

Directors Statement

Nowadays, Russia’s past is a central topic of disputes and discord. The fixation on the catastrophe that was endured in the last century does not appear to be healthy—society is paralyzed and unable to think about the present, much less the future. The flooding of Mologa in the 1930s is an open wound, even more so because there are still living people who were born in that city and evicted. Moreover, the resettlement and flooding took place against the backdrop of the dekulakization and repression of their families, and the formation of the Gulag to build the Rybinsk Reservoir, which needed to be completed after World War II started. What happens to someone who survives these catastrophes; what does he remember about them, and what do we remember about them today? The issue of memory is the film’s pervasive theme. The coexistence of incompatible phenomena in one’s memory is paradoxical: you can lose your father in the Gulag and call this “an excess”; you can know that it was prisoners who built the HPP and believe this to be justified by the needs of the government; you can lose your parents in the purges but consider Stalin an “effective manager.”. The anonymous Gulag cemeteries around Rybinsk call to mind the “zones” into which one can be led only by a stalker who is a student of local history in hopes of tracking down just one grave with a headstone. But the city’s residents do not know (and do not want to know) about them. The privatization of memory by a variety of institutions—from bureaucrats to the Russian Orthodox Church—in a strange way intertwines with the personal memories of witnesses; the words of a young contemporary historian could have been spoken in the propaganda films of the Stalin era and are utterly in tune with them. I could not pass up such material. The four days spent roaming the “zone” with a “stalker” forged the rhythm of the film and its shots. It has been known since ancient times that ancestors who are not buried, who are deprived of a place of commemoration, remain among the living. This is likely occurring with the Gulag cemeteries that are acknowledged by no one, cemeteries whose “inhabitants,” contrary to the will of the majority, are still among us and do not release us.

Director: Dmitry Boulba

Producer: Dmitry Boulba